Leeham News and Analysis

There's more to real news than a news release.

Leeham News and Analysis

Leeham News and Analysis

- The Boeing 767 Cross Section, Part 1 November 24, 2022

- Movie Review: Devotion November 21, 2022

- China will accelerate development of its commercial aerospace sector November 21, 2022

- Bjorn’s Corner: Sustainable Air Transport. Part 46. eVTOL comparison with helicopter November 18, 2022

- The economics of a 787-9 and A330-900 at eight or nine abreast November 16, 2022

Looking ahead in 2015 in commercial aviation

Here’s a visualization of events to look for in commercial aviation in 2015.

Posted on December 26, 2014 by Scott Hamilton

Airbus, Boeing, Bombardier, CFM, China, Comac, CSeries, Embraer, GE Aviation, Mitsubishi, Paris Air Show, Pratt & Whitney, Rolls-Royce

767-2C, A320NEO, A350-1000, A350-900, A380neo, air force tanker, Airbus, Boeing, Bombardier, CFM, CSeries, E-Jet E2, Embraer, GTF, KC-46A, LEAP, MC-21, Mitsubishi, MRJ, Pratt & Whitney, Qatar Airways, Rolls-Royce, Trent XWB

Boom times leads to looming cash flow shortfall across OEMs

Subscription Required.

Introduction

Dec. 16, 2014: There have been record aircraft orders year after year, swelling the backlogs of Airbus and Boeing to seven years on some product lines, Bombardier’s CSeries is sold out through 2016, Embraer has a good backlog and the engine makers are swamped with new development programs.

So it is with some irony that several Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) are warning of cash flow squeezes in the coming years.

Summary

- With so many development programs in the works, the prospect of new airplane and engine programs are being trimmed.

- Most airframe and engine OEMs under pressure.

- The full impact of the pending cash flow squeeze hasn’t been appreciated by the markets yet.

Posted on December 16, 2014 by Scott Hamilton

Airbus, Boeing, Bombardier, CFM, CSeries, Embraer, GE Aviation, Irkut, Mitsubishi, MTU, Premium, Rolls-Royce

787-10, A320NEO, A330neo, A350, A380, A380-900, A380neo, A400M, air force tanker, Airbus, Boeing, Bombardier, C-17, CFM, Comac, E-Jet E2, Embraer, GE Aviation, GE9X, GTF, Irkut, KC-390, KC-46A, LEAP, Mitsubishi, MTU, Pratt & Whitney, Rolls-Royce

New UTC CEO throws cold water on PW GTF growth

The new chief executive officer of United Technologies Corp., Gregory Hayes, threw cold water on hopes and dreams of Pratt & Whitney, a subsidiary, that the successful small- and medium-sized Geared Turbo Fan will grow into the wide-body market.

Aviation Week just published an article in which all three engine OEMs were reported to be looking at a 40,000 lb engine that would be needed to power a replacement in the category of the Boeing 757 and small 767. Hayes did not specifically rule out a 40,000 lb engine, leaving PW’s potential to compete for this business unclear.

Hayes has been CEO for two weeks. He was previously CFO. He made his remarks in a UTC investors event last night. The Hartford Courant has this report.

Hayes’ remarks were in response to a question from an analyst about research and development expenses. Here is his reply, from a transcript of the event:

Posted on December 12, 2014 by Scott Hamilton

Boeing, Bombardier, CFM, Comac, CSeries, Embraer, Irkut, Mitsubishi, Pratt & Whitney, Rolls-Royce

737 MAX, 757, 757 replacement, 767, 767 replacement, A320NEO, Alain M. Bellemare, Bombardier, C919, CFM, Comac, CSeries, E-Jet E2, Embraer, GE Aviation, Gregory Hayes, GTF, Irkut, MC-21, Mitsubishi, MRJ, Pratt & Whitney, United Technologies

737 MAX 8 could be enabler for some LCC Long Haul

Subscription Required

By Scott Hamilton and Bjorn Fehrm

Introduction

Figure 1. Nominal range of 737 MAX 8 from Oslo Source: Great circle mapper, Boeing. Click on Image to enlarge

Dec, 8, 2014:The Boeing 737-8 MAX is the successor to the 737-800 and has largely been thought of in this context.

Our analysis, prompted by Norwegian Air Shuttle (NAS) plans to use Boeing 737-8 MAXes to begin trans-Atlantic service on long, thin routes, comes up with a conclusion that has gotten little understanding in the marketplace: the 8 MAX has enough range and seating to open a market niche below the larger, longer-legged 757, and the economics to support profitable operations for Low Cost Carriers interested in some trans-Atlantic routes or destinations beyond the range of the -800.

Summary

- We based our analysis on our proprietary, economic modeling, assumed Norwegian cabin configuration standards.

- We compared the operating costs of the 737-8 with Norwegian’s present long haul aircraft 787-8 in a similar cabin configuration.

- The comparison range is the max endurance range for an LCC long haul 737-8, eight hours or 3,400nm air distance (no wind included).

Fundamentals of airliner performance, Part 5; Approach and landing

By Bjorn Fehrm

Dec. 2, 2015: The time has now come to cover descent and landing in our  articles around airliner performance. As many aspects of descent are similar to climb we will repeat a bit what we learned in Part 4:

articles around airliner performance. As many aspects of descent are similar to climb we will repeat a bit what we learned in Part 4:

- For high speed operation the pilots fly on Mach as this gives him maximum information around possible effects on the aircraft when he is close to the high speed limit, the maximum Mach number. Beyond this the aircraft gets into supersonic effects like high speed buffeting or unsteady flight.

- For operations under the cross over altitude for Mach 0.78 to 300 kts IAS the pilot flies on Indicated Air Speed (IAS) which gives him maximum information how the aircraft reacts should he go close to the aircraft’s lower speed limits.

Lets now start to go through the steps that our 737 MAX 8 performs after leaving its cruise altitude.

Posted on December 2, 2014 by Bjorn Fehrm

Oil heading toward $40? Economist still thinks so, with caveats; and: NTSB issues 787 battery report, Azul’s A320/CFM order

Dec. 1, 2014: Adam Pilarski, an economist for the consulting firm Avitas, predicted several years ago that the price of oil would drop to $40bbl. Few believed him.

Oil hit $66 this week, on a steady decline over the past months, and, according to an article by Bloomberg News, could be on its way to $40.

Pilarski, who originally made his prediction in 2011 at a conference organized by the International Society of Transport Aircraft Traders (ISTAT). He predicted this price by October 2018.

In an interview with Leeham News today, Pilarski concurs that oil may hit $40 soon, though he believes the low end will be in the $40-$50 range. The low price will not for the reasons he outlined in 2011 and neither will it stay at or near $40 for long.

Posted on December 1, 2014 by Scott Hamilton

Fundamentals of airliner performance, Part 4

By Bjorn Fehrm

Nov. 25, 2014: In our article series around the performance of a modern airliner we have now come to the climb after takeoff.  We started with cruise as this was simplest because the aircraft is flying in steady state, then we looked at the modern turbofan and how this is affected by both altitude and speed. We then examined how this affects the takeoff and today we continue with the climb after takeoff.

We started with cruise as this was simplest because the aircraft is flying in steady state, then we looked at the modern turbofan and how this is affected by both altitude and speed. We then examined how this affects the takeoff and today we continue with the climb after takeoff.

Before we start, let’s sum up a few points we need for today:

- Drag is the one thing we always need to be aware of as this regulates how much excess power we have in different flight situations and therefore if we can stay on our altitude or climb.

- Drag diminishes with altitude as the airs density diminishes and thereby our dominant drag component, air friction against our aircraft’s skin. This is the major component of the aircraft’s dominant drag, parasitic drag.

- Our lift force is generated by forcing air downwards and this causes induced drag as this downwash cost energy to generate and maintain. Induced drag is mitigated by a wing with a large span.

Posted on November 25, 2014 by Bjorn Fehrm

Lufthansa to use A340s in “lower cost” operation; our analysis against the 787

Subscription required.

By Scott Hamilton and Bjorn Fehrm

Introduction

Low cost long haul service is gaining traction, but previous efforts proved difficult to be successful.

Dating all the way back to Laker Airways’ Skytrain and the original PeoplExpress across the Atlantic, airlines found it challenging to make money.

More recently, AirAsiaX retracted some of its long-haul service, withdrawing Airbus A340-300 aircraft when they proved too costly. The airline recast its model around Airbus A330-300s as an interim measure, unable to fly the same distances as the longer-legged A340. AirAsiaX ordered the Airbus A350-900 and now is a launch customer for the A330-900neo.

Cebu Pacific of the Philippines is flying LCC A330-300 service to the Middle East. Norwegian Air Shuttle famously built its entire LCC long haul model around the Boeing 787, initiating service with the 787-8 and planning to move to the 787-9.

Cebu Pacific of the Philippines is flying LCC A330-300 service to the Middle East. Norwegian Air Shuttle famously built its entire LCC long haul model around the Boeing 787, initiating service with the 787-8 and planning to move to the 787-9.

Canada’s WestJet is leasing in four used Boeing 767-300ERs to offer LCC service,

Legacy carrier Lufthansa Airlines plans to use fully depreciated A340-300s to begin “lower cost” (as opposed to “low cost”) long haul service. LH says the fully depreciated A340s come within 1%-2% of the cost per available seat mile of the new, high capital-cost 787s.

Summary

- AirAsiaX’s A340 LCC long haul service proved unprofitable. Can Lufthansa’s similar service with fully depreciated A340s work?

- Our analysis shows that it can. It can even support the lease rates that would be charged for a 10 year old A340 if the fuel price remains at the present level.

- When doing the research for this article and going through the results of our proprietary model we started to ask ourselves, is the A340-300 the ugly duckling of the airline market?

Posted on November 19, 2014 by Scott Hamilton

Airbus, Airlines, Boeing, CFM, Premium, Rolls-Royce

747, 757, 767-300ER, 787, A330-900, A330-900neo, A340, A350-900, AirAsiaX, Airbus, Boeing, Canadair CL-44, Cebu Pacific, CFM, DC-10, DC-8-63, Douglas, Icelandair, Laker Airways, Loftleider, Luftansa Airlines, McDonnell Douglas, Norwegian Air, PeoplExpress, Rolls-Royce, WestJet

Fundamentals of airliner performance, Part 2.

By Bjorn Fehrm

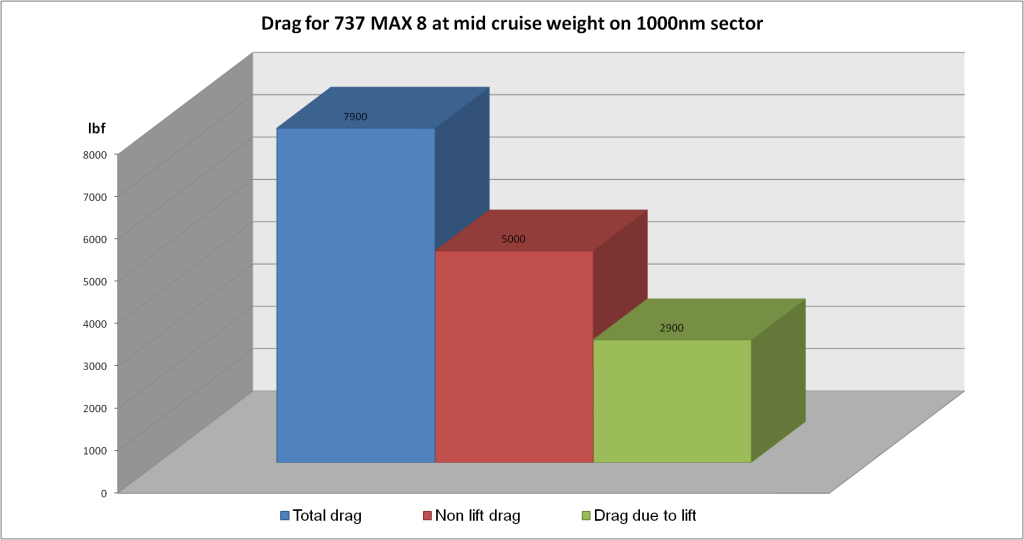

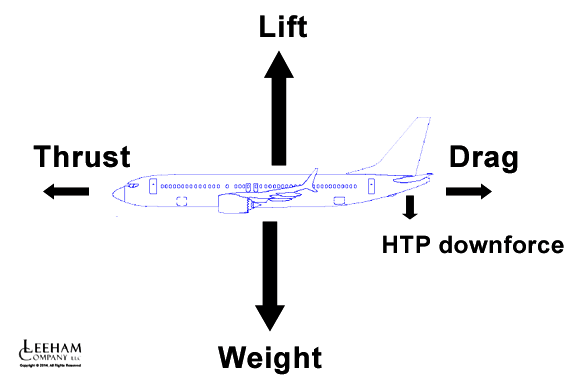

In our first article on how to understand the fundamentals that make up airliner performance we defined the main forces acting on an aircraft flying in steady state cruise. We used the ubiquitous Boeing 737 in its latest form, the 737 MAX 8, to illustrate the size of these forces.

Here a short recap of what we found and then some more fundamentals on aircraft’s performance, this time around the engines:

When flying steady state (Figure 1) we only need to find the aircraft’s drag force to have all important forces defined.

The lift force is given as equal to and opposite to the aircraft’s weight and the tail downforce that we need to add to this was small. We also presented the two classes of drag that we will talk about:

- Drag independent of lift or as we often call it drag due to size as almost all drag components here scale with the aircraft’s size.

- Drag due to lift or drag due to weight as we call it as this drag scales with weight when one flies in steady state conditions.

We could see that the aircraft’s flight through the air created a total drag force of 7900 lbf, Figure 2 ( lb with an f added as we prefer to write it as this is a force and not a measure of mass. Mass we denote with just lb or the metric units kg or tonne = 2205 lb).

Figure 2. Drag of our 737 MAX 8 and how it divides between lift and non lift drag. Source: Leeham Co.

We also learned that if the drag is 7900 lbf then the engine thrust is opposite and equal. It is then 3950 lbf per engine when cruising at our mean cruise weight of 65 tonnes or 143.000 lb on our 1000 nm mission. Drag due to size consumes 63% of our thrust and drag due to weight 37%. Read more

Posted on November 13, 2014 by Bjorn Fehrm

Email Subscription

Twitter Updates

My TweetsAssociations

Aviation News-Commercial

Commentaries

Companies-Defense

Resources

YouTube

Archives

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- July 2008

- June 2008

- May 2008

- April 2008

- March 2008

- February 2008

Fundamentals of airliner performance, Part 3

By Bjorn Fehrm

In our first article about how to understand the performance of a modern airliner we defined the main forces that are acting on an aircraft flying in steady state cruise. In our clinic we use the ubiquitous Boeing 737 in its latest form, the 737 MAX 8, to illustrate our case. In the second article we introduced the aircraft’s engines and understood how they function by pumping air backwards faster than the aircraft’s speed and therefore generating thrust as air is in fact quite heavy. We also looked at the influence of flight altitude on the performance of the aircraft.

In the second article we introduced the aircraft’s engines and understood how they function by pumping air backwards faster than the aircraft’s speed and therefore generating thrust as air is in fact quite heavy. We also looked at the influence of flight altitude on the performance of the aircraft.

In short we can conclude our findings so far:

Having covered the most important aspects of cruise we will today look at takeoff, a subject with a lot of aspects. Read more

Leave a Comment

Posted on November 19, 2014 by Bjorn Fehrm

Boeing, CFM, Leeham News and Comment, Uncategorized

737 MAX, Boeing, CFM, CFM Leap-1B